A Unified Biochemical Paradigm of FQAD

From Mitochondrial Toxicity to Vitamin B6 Metabolism Dysfunction

For decades, mainstream research attributed Fluoroquinolone-Associated Disability (FQAD) to nucleus damages and mitochondria, specifically mtDNA damages. In this view, Fluoroquinolones caused permanent DNA adducts, leading to impaired gene expression. This perspective garnered significant attention and financial resources (and continues to do so) but yielded limited results and numerous unanswered questions, such as whether FQs specifically target genes in the collagen synthesis pathway through DNA adducts.

In late 2023, I proposed a hypothesis that diverged from mainstream research, suggesting that FQAD was primarily caused by persistent biochemical disruptions at the enzymatic level.

My central thesis was that the toxicity of FQ primarily stemmed from enzymatic inhibition, which manifested in two primary axes:

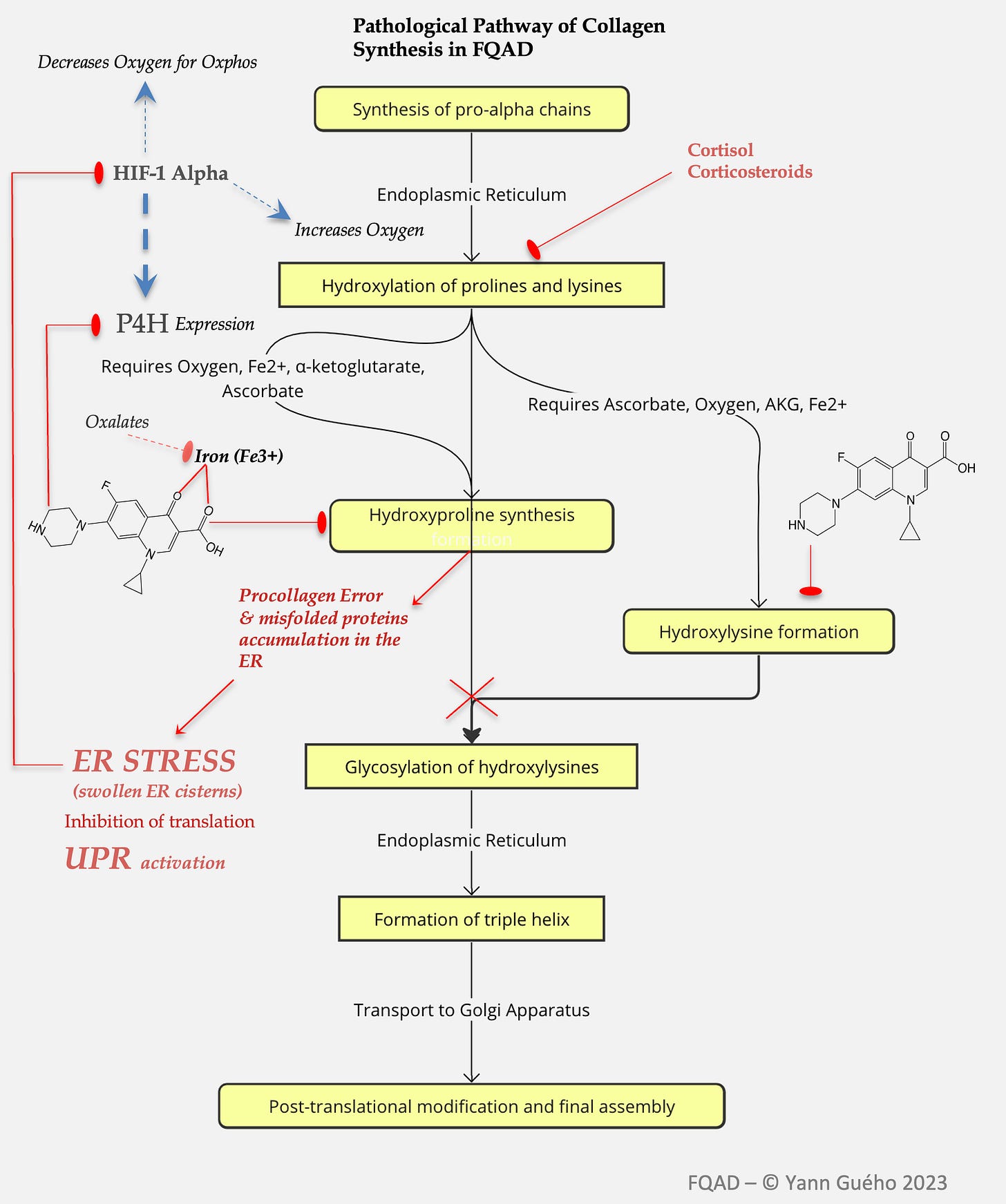

1) An inhibition of enzymes involved in collagen synthesis.

Based on the seminal work of Badal et al. (2015) and Michalak et al. (2017), I observed that fluoroquinolones exerted a potent inhibition of enzymes belonging to the 2-OGDD (2-oxoglutarate dependent dioxygenases) enzyme family. This inhibition was achieved by binding essential metals such as iron (Fe³⁺), magnesium (Mg²⁺), copper (Cu²⁺), and zinc (Zn²⁺) via their carboxylate and keto groups. Notably, these stable bonds formed insoluble crystalline complexes that could persistently obstruct enzyme active sites, even impeding intracellular phase II detoxification. Furthermore, these crystals were believed to impair enzymes like prolyl-4-hydroxylase (P4H), a crucial player in collagen maturation, by both depleting bioavailable iron and physically blocking catalytic centers..

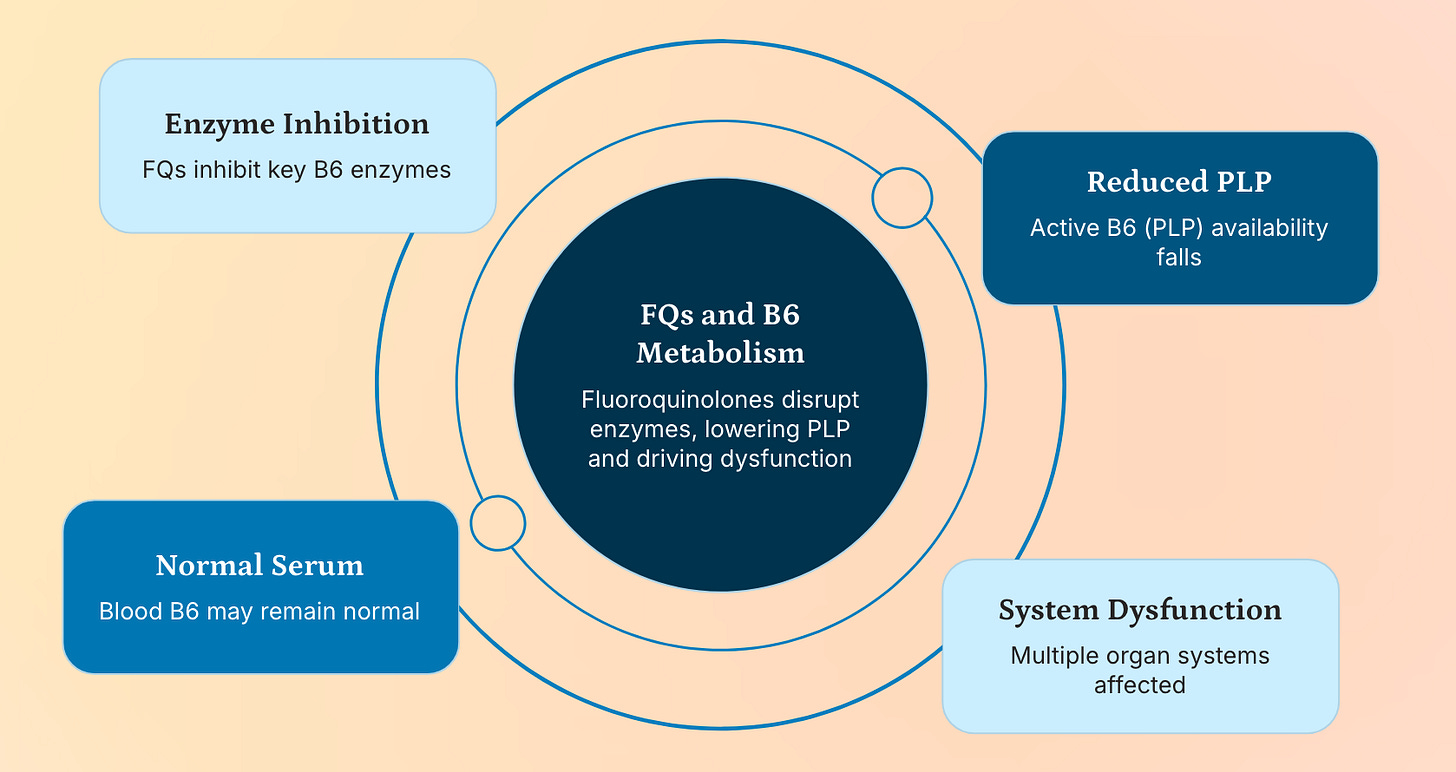

2) An inhibition of enzymes involved in the synthesis of pyridoxal-5-phosphate.

My observation was that fluoroquinolones (FQs) may induce a functional deficiency in pyridoxal-5-phosphate (PLP), the active coenzyme form of vitamin B6, by interfering with key enzymes in its metabolic pathway: pyridoxal kinase (PdxK), pyridoxine phosphate oxidase (PNPO), and potentially alkaline phosphatase. This hypothesis emerged from a striking overlap—34 common clinical dysfunctions—observed in FQAD patients mirrored those seen in documented PLP deficiency, including peripheral neuropathy, cognitive impairment, mood disorders, collagen dysregulation, and impaired methylation.

Yet, despite the plausibility of this model, it left many questions unanswered: Why do symptoms persist for years after drug clearance? Why are some individuals disproportionately affected, especially women and those with certain skin pigmentation profiles? And why do standard supplementation strategies (e.g. magnesium) often fail to alleviate symptoms?

These unresolved issues were dramatically illuminated in April of this year, with the publication of Reinhardt et al.’s study from the Technical University of Munich, a breakthrough that not only validated my long-standing suspicion about off-target enzyme inhibition but also provided a new mechanistic framework for understanding FQAD at the molecular level.

Reinhardt et al. (2025): A Paradigm Shift in Understanding FQ Toxicity

Reinhardt and colleagues conducted a rigorous investigation into the mitochondrial toxicity of fluoroquinolones, focusing specifically on ciprofloxacin and levofloxacin, using a groundbreaking experimental design: they compared the effects of standard FQs with chemically modified analogues engineered to be incapable of metal chelation.

This approach allowed them to isolate the intrinsic, metal-independent toxicity of FQs.

Their findings were revolutionary:

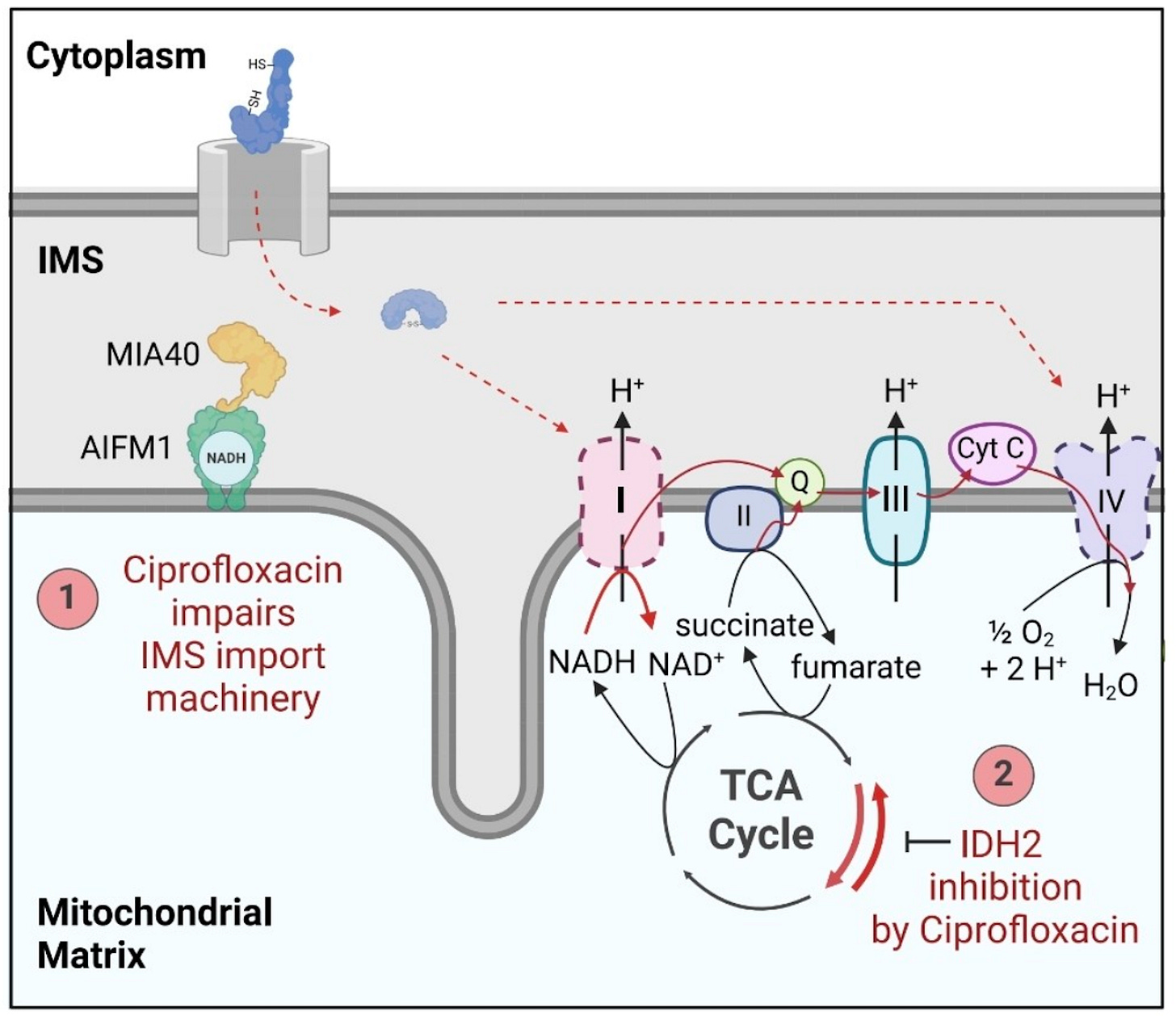

Fluoroquinolones directly inhibit two essential mitochondrial enzymes:

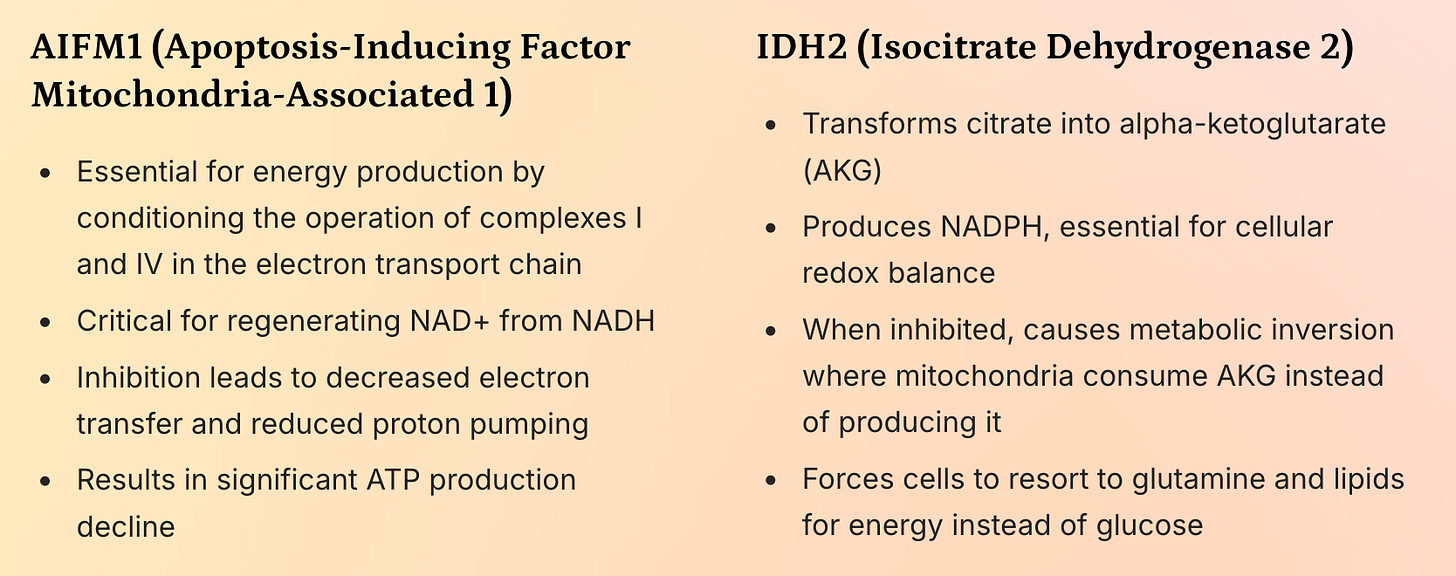

AIFM1 (Apoptosis-Inducing Factor Mitochondria-Associated 1): A flavoprotein crucial for electron transfer in the respiratory chain and NAD⁺ regeneration.

IDH2 (Isocitrate Dehydrogenase 2): A key enzyme in the Krebs cycle that converts isocitrate to α-ketoglutarate (AKG) while producing NADPH.

Fig. (Reinhardt et al. 2025)

They found that the inhibition of AIFM1 and IDH2 led to:

Severe reduction in Complex I and IV activity, impairing oxidative phosphorylation.

A dramatic drop in the NAD⁺/NADH ratio, indicating failure to regenerate oxidized cofactors.

Metabolic reprogramming: Mitochondria reversed their function—consuming AKG and producing citrate instead of the other way around. This mirrors metabolic shifts seen in type II diabetes and suggests a systemic failure in glucose oxidation.

A shift toward reliance on glutamine and lipids for energy, consistent with the observed metabolic exhaustion in FQAD patients.

This study delivered two critical revelations:

FQs have intrinsic, off-target toxicity independent of metal chelation—a phenomenon previously unproven.

Their mechanism involves direct binding and inhibition of mitochondrial enzymes, particularly those dependent on NAD⁺/NADH or NADP⁺/NADPH cofactors.

Molecular Mimicry: A Unifying Hypothesis Across Systems

The most profound insight from Reinhardt et al. lies in the structural similarity between fluoroquinolones and essential cellular cofactors.

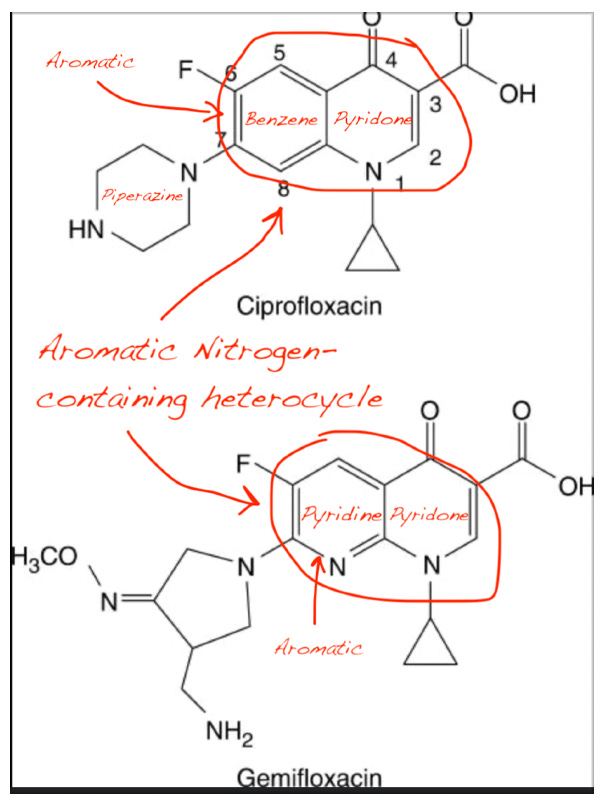

Upon close examination, I found that:

NAD⁺, NADH, and NADP⁺ all contain a nitrogen-containing aromatic heterocycle (nicotinamide ring).

Ciprofloxacin and other FQs possess a fused aromatic heterocyclic core with nitrogen atoms (quinolone ring).

Pyridoxal and PLP also feature a pyridine ring, another nitrogen-containing heterocycle.

This structural convergence suggests molecular mimicry: fluoroquinolones may competitively bind to the active sites of enzymes that normally recognize NAD⁺/NADH or PLP due to their shared aromatic nitrogen motif. This explains why:

FQs inhibit AIFM1 (an NAD⁺/FAD-dependent enzyme).

FQs inhibit IDH2 (a NADP⁺-dependent dehydrogenase).

FQs could similarly interfere with PLP-dependent enzymes, including those in vitamin B6 metabolism.

This hypothesis aligns perfectly with my 2023-24 work. If fluoroquinolones bind to the active sites of PdxK (which phosphorylates pyridoxal) or PNPO (which oxidizes pyridoxine phosphate to PLP), they would prevent the formation of active PLP, leading to a functional deficiency even if plasma levels appear normal.

The Paradox of Normal or Elevated PLP Levels in FQAD Patients

One of the most confounding clinical observations is that many FQAD patients exhibit normal or even elevated serum PLP levels—a finding often interpreted as evidence against B6 deficiency. However, this paradox dissolves when we consider intracellular trafficking and enzyme competition.

PLP is not freely diffusible; it must be actively transported into cells and delivered to target enzymes.

If PdxK or PNPO are inhibited by fluoroquinolones, pyridoxal cannot be converted to PLP, even if precursor levels are high.

Furthermore, PLP-dependent enzymes (e.g., transaminases, decarboxylases) may be unable to function if FQs occupy their active sites, creating a “pseudo-deficiency” despite adequate circulating PLP.

Thus, plasma levels are misleading—they reflect total pool size but not functional availability. This is analogous to how high insulin levels don’t prevent hyperglycemia in type II diabetes due to receptor resistance.

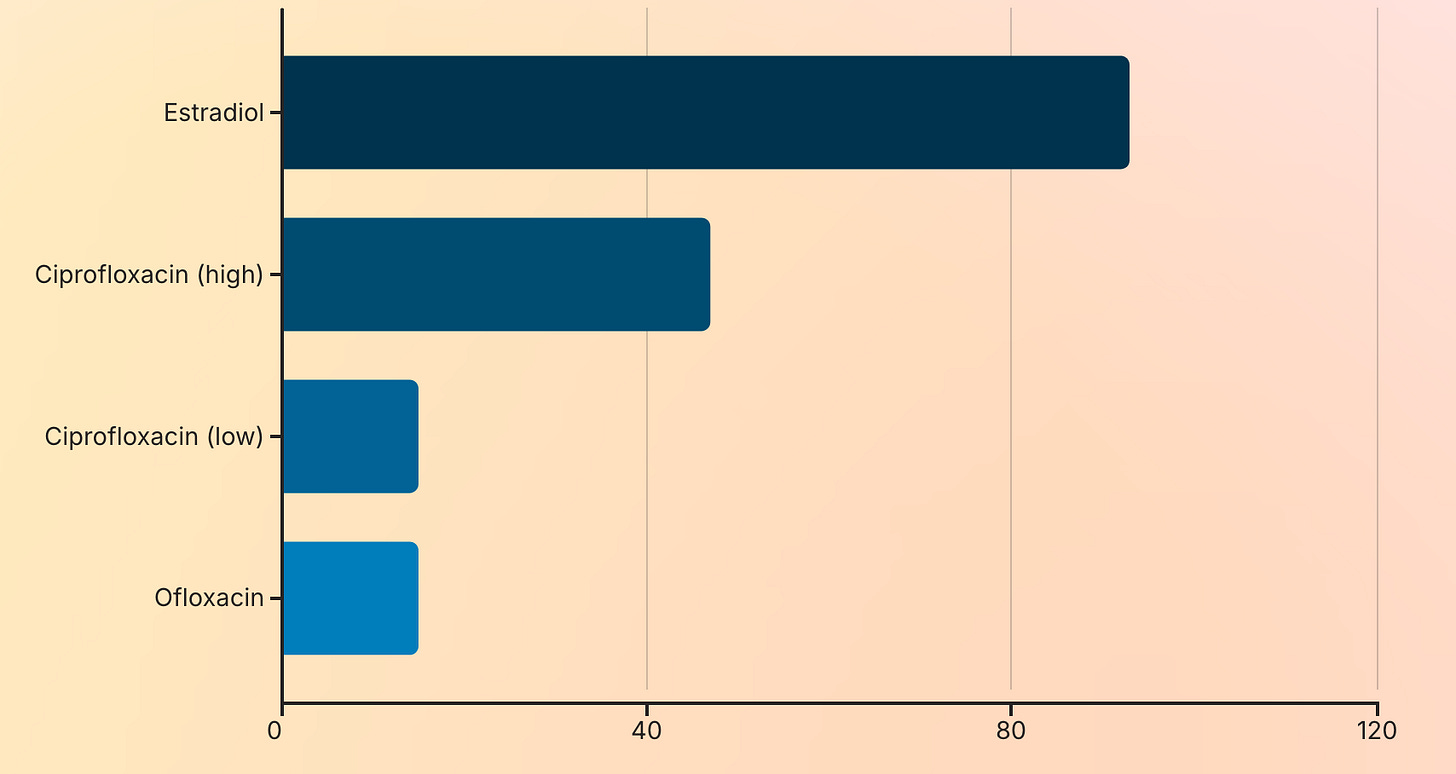

Aldehyde Oxidase (AO): A Hidden Player in FQAD Pathogenesis

An additional layer of complexity emerges when we consider aldehyde oxidase (AO), a cytosolic enzyme involved in drug metabolism and detoxification.

AO metabolizes aldehydes, including pyridoxal (the precursor to PLP).

Crucially, AO recognizes nitrogen-containing aromatic heterocycles—a structural feature shared by FQs, NAD⁺ derivatives, and pyridoxal.

A 2004 study by Obach et al. confirmed that ciprofloxacin inhibits AO activity by 15–47%, and ofloxacin similarly reduces its function.

This inhibition has serious implications:

Impaired detoxification of aldehydes → accumulation of toxic metabolites.

Reduced clearance of FQs themselves → prolonged exposure and crystallization in tissues.

Compromised metabolism of endogenous aldehydes (e.g., from lipid peroxidation) → oxidative stress and cellular damage.

But here’s where the gender disparity in FQAD becomes explainable:

Estradiol, a primary female sex hormone, is itself a potent inhibitor of aldehyde oxidase—up to 93% inhibition in vitro.

Therefore, women naturally have lower AO activity than men.

When combined with FQ-induced inhibition (via competitive binding), the result is a double hit on detoxification capacity.

This explains why FQAD affects women at significantly higher rates than men—not just due to lower iron stores, but because of inherent differences in xenobiotic metabolism.

Moreover, this extends to other Phase II detoxification enzymes like UGT1A, which are also inhibited by estradiol. This creates a broader detoxification deficit in women, rendering them more vulnerable to environmental and pharmaceutical toxins.

Genetic, Pigmentary, and Environmental Dimensions of FQAD Risk

Beyond gender, there is growing evidence for genetic and pigmentation-based disparities in FQAD susceptibility.

Melanin, the pigment responsible for skin color, functions as a Phase III detoxification system—a biological sink capable of binding and sequestering xenobiotics.

Melanin-producing cells (melanocytes) are highly metabolically active and may absorb FQs via endocytosis or membrane transport.

Over time, melanin can incorporate these molecules into its polymer matrix—effectively trapping them in the skin.

This may explain why dark-skinned individuals appear to experience fewer or less severe FQAD symptoms: their melanin acts as a protective buffer, reducing systemic exposure.

Conversely, white or fair-skinned individuals—especially women—have lower melanin reserves and may therefore:

Experience higher systemic exposure to FQs.

Be less able to sequester and excrete them via the skin.

Face greater risk of crystallization in deep tissues (e.g., tendons, nerves, brain).

This suggests a genotype of FQAD: individuals with low melanin production (e.g., Caucasians), female sex, and genetic variants affecting AO or B6 metabolism are at highest risk.

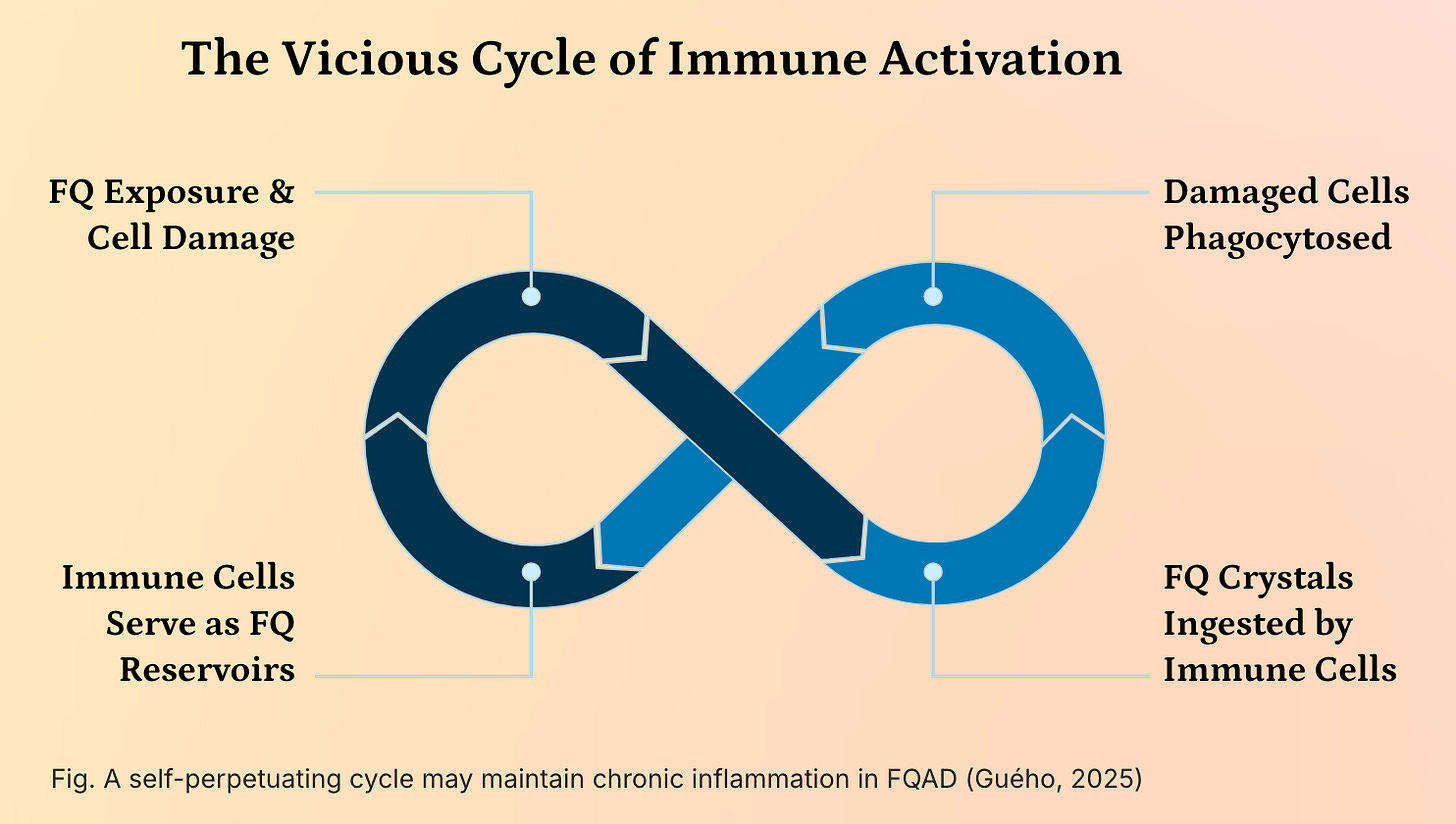

Self-perpetuating vicious cycle of immune activation

A self-perpetuating vicious cycle of immune activation may underly the chronicity and systemic nature of Fluoroquinolone-Associated Disability (FQAD), driven by the persistent presence of insoluble fluoroquinolone-metal (e.g., iron, aluminum) crystals within the body.

These crystals, formed due to the high stability and resistance to cellular degradation of FQ-metal complexes, are not efficiently cleared and accumulate in long-lived cells such as sensory neurons and connective tissues. When these cells undergo apoptosis or necrosis, their contents—including the toxic crystals—are engulfed by phagocytic immune cells, primarily macrophages and neutrophils. This phagocytosis temporarily sequesters the crystals, but as the immune cells themselves eventually die, they release the crystals back into the extracellular environment, where they are taken up by new phagocytes.

This creates a self-sustaining cycle of cellular turnover and crystal redistribution, effectively turning immune cells into transient reservoirs that perpetuate the exposure of the immune system to a persistent, non-degradable foreign body. The chronic presence of these crystals triggers sustained activation of pattern recognition receptors (e.g., NLRP3 inflammasome), leading to the continuous release of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6, resulting in chronic low-grade inflammation and immune dysregulation. This persistent immune activation not only contributes to tissue damage and pain but may also drive autoimmunity and exacerbate neurological and metabolic symptoms, thereby reinforcing the systemic and refractory nature of FQAD. The inability of the immune system to resolve the threat, combined with the structural stability of the crystals, transforms FQAD into a condition of chronic immune stimulation, where the body’s own defense mechanisms become a key driver of ongoing pathology.

Implications for Treatment and Future Research

The convergence of Reinhardt et al.’s findings with my earlier work points to a unified biochemical model of FQAD:

FQs cause long-term disability not by damaging DNA or mitochondrial DNA, but through direct inhibition of critical enzymes—both in mitochondria and in vitamin B6 metabolism—via molecular mimicry of NAD⁺/NADH/NADP⁺ and PLP.

This reframes treatment strategies and points toward the needs of “in silico” molecular docking simulations in order to predict how FQs bind to PdxK, PNPO, AIFM1, IDH2, and AO—identifying precise binding pockets and guiding targeted therapeutics.

Future goals include:

Conducting 3D docking studies to model FQ interactions with key enzymes.

Investigating pharmacogenomic profiles associated with high-risk genotypes (e.g., AO variants, UGT1A polymorphisms).

Exploring melanin-based detoxification pathways as a potential route for FQ excretion and therapeutic intervention.

If you find my work helpful, please consider subscribing or supporting my research with a coffee ☕️ 🙂

Conclusion: From Hypothesis to Evidence-Based Paradigm

My 2024 study, initially dismissed as speculative, has now been validated by Reinhardt et al.’s rigorous research and Obach et al. (2004). The discovery of off-target, metal-independent toxicity toward mitochondrial and cytosolic enzymes is not an exception—it is the rule. Fluoroquinolones are not just metal chelators; they are molecular mimics, capable of disrupting multiple enzymatic systems through structural similarity. Their presence as unsoluble crystals formed with metals may explain their long term retention.

This new paradigm:

Explains the persistence of symptoms long after drug clearance.

Clarifies why supplementation fails in many cases.

Reveals the true nature of PLP deficiency: not a lack of precursor, but a failure to activate and utilize it.

Highlights the interplay between gender, genetics, pigmentation, and detoxification capacity in determining FQAD risk.

Ultimately, FQAD is not a disease of the nucleus or mitochondrial DNA—it is an enzymopathy. The solution lies not in gene therapies, but in targeted metabolic support, computational drug modeling, and a deep understanding of molecular mimicry in human biochemistry.

Thank you so much for pursuing and sharing this important work! As someone who suffers from both FQAD and B6T, I am so grateful to you for developing this theory to explain how they are connected.